Amid wild Atlantic waters

the UK's seabirds struggle for survival

we plunge into their world

Seabird secrets

Dominic Couzens, March 2023

Let’s follow one of the herring gulls in our imagination. After finding nothing offshore while following the boat, it desultorily leaves the flock and makes its way back towards the nearby cliffs. But en route, something white glints in its eye and it decides to change course. The scene comes into view, a melée of birds congregating on the sea about 500m offshore. Our herring gull rushes to join the feeding frenzy on the shoaling fish. White attracts white, and within minutes dozens of gannets are diving overhead, kittiwakes are plunging from a moderate height and the herring gulls grab from the surface or steal from others.

The opportunity is fleeting. Within minutes the fish have dispersed. The excitement dissipates as quickly as the splash of a hunting bird. But everyone present has food for their chicks.

As these fortunate birds fly back to the coast, another kittiwake passes through and, having missed the ephemeral bonanza, ploughs on towards the open sea. Over this apparently featureless void, it will search for another melée, or look for subtle, tell-tale signs of food. There might be a disturbance on the water where an upwelling on the seabed brings nutrients within reach and tickles the water surface, for example, or a whale is feeding and does the same. Soon our human-covered beach lies far in the distance.

After a few minutes the kittiwake reaches a sort of seabird highway. Parties of guillemots, razorbills and puffins are passing, in small flocks, some going out to sea, others returning, all in a narrow stream over a few hundred metres of water. The auks are on commuting duties feeding their young, and word has got out (from birds observing each other), that there is good feeding 30km further out. In our imagination we take a slip road on to this line of traffic and follow the auks as they flap hard on their tiring journey. Land now disappears from view completely. We have entered the poorly known realm of the UK’s waters.

As the afternoon draws on, our auks have fed underwater and start their homeward journey. At one point they cross paths with a group of Manx shearwaters, which have been feeding out in the open Atlantic. We peel off to follow these as they make short flaps and glides, rocking from side to side, their wing tips almost touching the water. Hour by hour they approach a small island that has been shaped by Atlantic winds and pounding storms. Uninhabited except by birds, the island has high cliffs and a soft centre topped by tussocks. The shearwaters, who know the way to go over the featureless water, settle offshore and wait for the short night.

It’s a familiar scene. In a seaside town, gulls are following a fishing boat to port on a summer afternoon. Nobody on the beach takes much notice, too concerned with their ice-creams, or keeping an eye on the kids. But if only they knew it, the birds in front of them were about to be part of a relay into the unknown, a tour that would lead to a world that few people know anything about.

Above: Gannets compete for food far offshore, beneath the clear Atlantic waters.

Dominic Couzens is a wildlife writer and tour leader living in Dorset. He is the author of numerous books on birds, mammals and invertebrates, and also writes for several magazines and newspapers.

As the light fades, the shearwaters fly to their burrows. For a while, the island resounds to the strange cries of seabirds, all making the same nocturnal appointments. The shearwaters make a loud, halting crowing, like a cockerel with asthma, while nearby storm petrels make a purring sound like an engine starting on a cold morning; meanwhile, their slightly larger cousins, the Leach’s petrels, intersperse a similar purring with the odd chuckle, as if making the punchline of a joke. All bring regurgitated mush from the sea to feed to their young, hidden in burrows blanketed by the darkness.

Our relay journey ends here, at a huge seabird city that comes awake at night. This is the UK’s most remote wildlife spectacular, thousands of voices yelling eerily in the summer twilight on a small rock far out in the oceans – as distant from our experience as any bird bonanza can be. Yet it is still, just about, part of the British Isles.

Above: A Kittiwake approaches the stacks of Boreray in St Kilda, home to the world’s largest gannetry of around 60,000 pairs.

‘Our relay journey ends here, at a huge seabird city that comes awake at night.’

Designined by nature: Gannet

Some seabirds pluck fish from the surface while others can dive to the seabed. How do they do it?

Trouble at sea

You might think that this faraway marvel would be an untroubled one. After all, out here on the edge, it barely whispers into the consciousness of the keenest of birders, let alone the general public, and you might innocently think that it was too secluded to be sullied by much human activity.

“Not all is well in the world of seabirds,” says Mark Bolton, sadly. Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB, he is all too aware of a declining trend among many of our key breeding species, from kittiwakes to Arctic skuas. As someone who has worked among the petrels, he is particularly concerned about them.

“Recent surveys have shown a sharp fall in the number of breeding pairs of Leach’s petrels throughout its range,” he says. “On St Kilda, our largest colony, numbers have fallen 68% between 1999–2000 and a survey in 2019. There are now only 8,900 pairs.”

These are significant losses to a seabird that breeds on the most isolated islands. “It is now globally Vulnerable,” adds Mark.

If the Leach’s petrel problem was isolated (and at least part of its decline is down to predation by another range-restricted species, the great skua), then concern would be ameliorated. But with several other species, such as Arctic skuas, also suffering steep falls, the race is on to find out more about our seabirds, and what threatens them in these faraway places.

Just recently, the Scottish Government has commissioned RSPB Conservation Science to place GPS trackers on St Kilda Leach’s petrels, to give clues about where they feed, and how they might be impacted by a range of factors, including light pollution, fishing and renewable energy developments.

It’s one of those projects that sounds easy. But in what Conservation Scientist Connie Tremlett describes as a “tough gig”, it involves night after night of trudging uphill for over an hour to the colony and then working all night, for 40 days.

“Leach’s petrels are only the size of a starling,” she says. “The GPS trackers are so small that their batteries run out quickly, and we can’t access them remotely, meaning that we have to catch the birds again to recover the data. It’s gruelling work.”

Despite the difficulties, the dark and two weeks of appalling weather, they managed to track 14 Leach’s petrels – the first time this has ever been done for the UK birds. The results are in their infancy, but they did discover that the birds were feeding up to 250 miles west, far out in the Atlantic Ocean.

‘It involves night after night of trudging uphill to the colony and working all night.’

“We think they are foraging beyond the shelf edge, the undersea cliff area where there are upwellings of currents,” says Mark. “We urgently need to do more work to find out what they are feeding on.”

Several related tracking studies have also shown that seabirds make long journeys to find food for their young. A recent study on Manx shearwaters on the west coast of Ireland found that adults with young sometimes travelled over 900 miles, and even as far as the Mid-Atlantic ridge, to look for food. They alternated short trips with long trips, up to 11 days, aiming for rich feeding grounds. In the meantime, the chick remained safe, if sometimes somewhat hungry, in the burrows, usually attended by a parent. The short trips occurred when the chicks needed feeding more urgently.

Recently, storm petrels on Mousa, in Shetland, were found to be travelling up to 185 miles south of the islands and were sometimes blown much further away by storms. “But now we know where they are going,” says Mark, “we can focus our conservation efforts on these areas.”

Another recent tracking study looked at three familiar cliff-nesting species: guillemots, razorbills and shag, that occasionally suffer from being caught in gill nets, which hang like curtains from the surface. Conservation Scientists Ian Cleasby and Linda Wilson tracked everything they could – where the birds go, how deeply they dived and at what time of day. They also tried to find records of human fishing activity to correlate when there might be a clash. Such efforts, despite the intense hard work, enable us to recognise what threats the birds face at sea.

How the RSPB

is helping

Burrowing deeper

RSPB biologist John Tayton creating artifical manx shearwater nest sites, Garbh Eilean, Shiant Isles, Outer Hebrides, Scotland.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse sagittis tempor est sed suscipit. Phasellus elementum est quis libero tristique convallis. Nulla ac metus auctor, mollis dui in, lobortis eros.

Morbi quis sem sed tellus facilisis egestas. Phasellus semper erat odio, facilisis viverra erat hendrerit eget. Vestibulum lacinia feugiat tincidunt.

Returning home

Manx shearwater adult returning to nest burrow at night. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse sagittis tempor est sed suscipit. Phasellus elementum est quis libero tristique convallis. Nulla ac metus auctor, mollis dui in, lobortis eros.

Call of the wild

Field assistant Lydia plays a tape of a Manx shearwater call at a potential burrow in the hopes of hearing a call back.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse sagittis tempor est sed suscipit. Phasellus elementum est quis libero tristique convallis. Nulla ac metus auctor, mollis dui in, lobortis eros.

People supporting seabirds ashore

The declines in seabird numbers are not all caused by what happens at sea – the security of the cliffs and burrows where the birds nest are just as important. And, to that end, the RSPB has been involved in a number of projects to try to rid islands of one of the birds’ main curses – rats, which eat seabirds, especially the young.

One of the most remarkable programmes has been on the Isles of Scilly, where Islands and Biosecurity Officer Jaclyn Pearson has not only had rats to deal with, but human beings, too!

“On St Agnes and Gugh we have the largest community-based rat eradication programme in the world,” she says. “There are 90 human inhabitants on the islands, and we have had to persuade every one of them to buy into the project. To protect the breeding Manx shearwaters, we have asked the owners of every dwelling to allow access for rat poison and other eradication measures. It’s been a huge, but successful task.”

People need to be convinced that the effort is worthwhile, but gradually the net worth of extra tourism, as well as the good feelings about helping the shearwaters themselves, has won people over.

It has also had extra benefits. “To cut off a potential food source for rats, we asked one of the farmers if they could ensure that they didn’t leave windfall apples on the ground,” says Jaclyn. “As a result, they picked them up and promptly began to sell apple juice, cider and even gin to tourists. The rat eradication programme was a catalyst for producing gin – that’s a result!”

All these projects are underpinned by the need for good censusing of seabird numbers. Anyone who has been to a large seabird colony is instantly overawed by the sheer hustle and bustle, the constant comings and goings and the overwhelming abundance. Many of us have wondered how they are ever counted.

One answer is to install high-definition cameras using time-lapse technology trained at seabird colonies that give a 4G link to seabird researchers. “Here in Scotland we have received funding from NatureScot Nature Restoration Fund to set up specially designed (Time-Lapse Systems) cameras trained on seabird colonies at the Mull of Galloway and at Fowlsheugh,” says Ellie Owen, RSPB Conservation Scientist. “The beauty of them is that the cameras are ultra-high resolution, so they are effective even if the nearest viewpoint is a long way from the colony. What’s more, they are autonomous, and we can leave them in place for a year or more. It’s a fantastic solution to difficult monitoring conditions. We are setting 10 more cameras up this year, giving us a clear view of birds that would once have been too far away to count.”

And how on earth do you count birds on an isolated island in the dark? “Recently, people have just had to visit in season and listen outside each burrow in a petrel or shearwater colony to see who responds to a playback of the call,” says Mark.

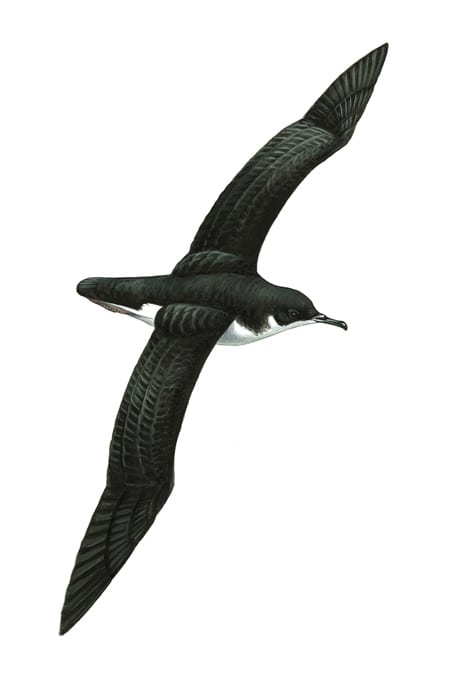

Manx Shearwater

The Manx shearwater is a small shearwater, with long straight slim wings, with black above and white below. It flies with a series of rapid stiff-winged flaps followed by long glides on stiff straight wings over the surface of the sea, occasionally banking or 'shearing'. It breeds in colonies in the UK, on offshore islands where it is safe from rats and other ground predators.

What they eat: Fish, especially herrings,

sardines and sprats.

UK conservation status: Amber

The seabirds of St Kilda

Hear my call

Storm petrel

A little bigger than a sparrow it appears all black with a white rump. Its tail is not forked, unlike Leach's petrel. In flight it flutters over the water, feeding with its wings held up in a 'V' with feet pattering across the waves. At sea it often feeds in flocks and will follow in the wake of ships, especially trawlers.

What they eat: Fish, plankton and crustaceans.

UK conservation status: Amber

Hear my call

Leach's petrel

The Leach's petrel is a starling-sized seabird. These birds are all black underneath and mostly black above, apart from a white rump. It has a forked tail. The white rump has a black line down it. Leach's petrels breed on remote offshore islands to the UK and feed out beyond the continental shelf.

What they eat: Crustaceans, molluscs and small fish.

UK conservation status: Red

Hear my call

Gannet

Adult gannets are large and bright white with black wingtips. They are distinctively shaped with a long neck and long pointed beak, long pointed tail, and long pointed wings. At sea they flap and then glide low over the water, often travelling in small groups. They feed by flying high and circling before plunging into the sea. They breed in significant numbers at only a few localities and so is an Amber List species.

What they eat: Fish.

UK conservation status: Amber

Hear my call

Kittiwake

Kittiwakes are gentle looking, medium-sized gulls with a small yellow bill and a dark eye. They have a grey back with white underneath. Their legs are short and black. In flight the black wing-tips show no white, unlike other gulls, and look as if they have been 'dipped in ink'. The population is declining in some areas, perhaps due to a shortage of sandeels. After breeding birds move out into the Atlantic where they spend the winter.

What they eat: Fish, shrimps and worms.

UK conservation status: Red

Hear my call

A helping paw from man's best friend

During lockdown, however, and inspired by a conversation with a warden on Ramsey Island in Wales, Mark Bolton decided to see whether he could enlist the services of a helper – his own pet golden retriever, Islay.

“In some parts of the world, sniffer dogs have been used to detect occupied burrows of endangered birds,” says Mark. “So, I trained Islay with storm petrel feathers to see whether she could do the same.”

So far, the results have been a great success. Two dogs have been used to indicate, to their handlers, whether burrows are occupied. The trials showed that Islay was able to distinguish between the scent of storm petrels and Manx shearwaters, which often share the same colonies.

Conserving seabirds is a tall order. The birds aren’t around breeding for long, they are inaccessible, not especially docile, and often nocturnal. It takes a lot of hard work to get any results at all.

“But we have to find out how to help them,” says Mark. “Our seabird colonies are some of the best in the world.”

And that’s true, even if most people remain oblivious to them, or the dramatic lives they lead as they soar from our shores and into the blue horizon.

Above: Seabird sniffer dog Islay, a Golden Retriever, is able to distinguish between Manx Shearwater and Storm Petrel by scent and identify occupied burrows.

3 ways to support seabirds…

1. Do a beach clean

One of the biggest threats to seabirds both in and out of the water is discarded marine plastic. Abandoned fishing nets (‘ghost nets’) are a leading cause of entanglement, along with discarded fishing line. Birds also swallow microplastics and even large objects like bottle tops, balloons and beach toys. Every object that washes up on our shores is potentially deadly to marine life, so next time you’re at the beach, set aside a few minutes to remove anything from the beach that doesn’t belong there – you’ll be directly saving seabird lives. Please leave seaweed, shells and stones in place though, as part of the intertidal ecoystem.

2. Visit a seabird colony

The most exciting way to learn more about the lives of seabirds is to visit a colony. The UK has some of the world’s most important breeding sites for a range of globe-trotting seabirds, and by immersing yourself in their cacophonous world you get to see, hear and even smell the daily lives of different species and how they interract. You’ll be hooked! The RSPB nature reserves at Bempton Cliffs (East Yorkshire) and South Stack (Anglesey) are both unforgettable July experiences.

3. Check your seafood

Overfishing (when fish are hunted faster than populations can recover) robs seabirds of their food, too. With the average person eating twice as much fish as 50 years ago, and our population having doubled in that time, overfishing is now the most serious threat to the survival of our oceans. If you do eat fish, look for the Marine Stewardship Council certification. The MSC works to rebuild marine habitats and ensure fishing is kept to sustainable levels.

Help the RSPB to save more seabirds

You gift to us will help us to continue to fight for nature and the wildlife you love.

Make a donation

You might also like

Looking for justice

Protecting our precious birds of prey from illegal persecution is a demanding job. Investigations Liaison Officer Jenny Shelton explores this shocking issue.

Wing and a prayer

Over freezing tundra and endless seas, Bewick’s swans make a perilous journey to our shores. Marianne Taylor discovers why fewer are making it.

Caught on camera

BBC’s Wild Isles series is celebrating Britain and Ireland’s spectacular wildlife like never before. Jamie Wyver speaks to the Silverback Films’ team.